The hidden stories of the cultural looting of Latin America

Ojo-publico.com presents a transnational investigation prepared by teams of journalists in five different countries. It reveals the figures and the most serious cases of trafficking of cultural heritage in Latin America, an activity that connects antique dealers and politicians in Buenos Aires to drug lords in Guatemala, and suspicious art collectors in Mexico to diplomats in Costa Rica and Peru. This report—which will have several submissions—also reveals an international art market scheme that permits the selling of stolen objects, taken from temples, public museums, and private collections. It is the first journalistic investigation on cultural trafficking involving big data. It also includes a database establishing the beginning of the first Latin American census of stolen cultural property.

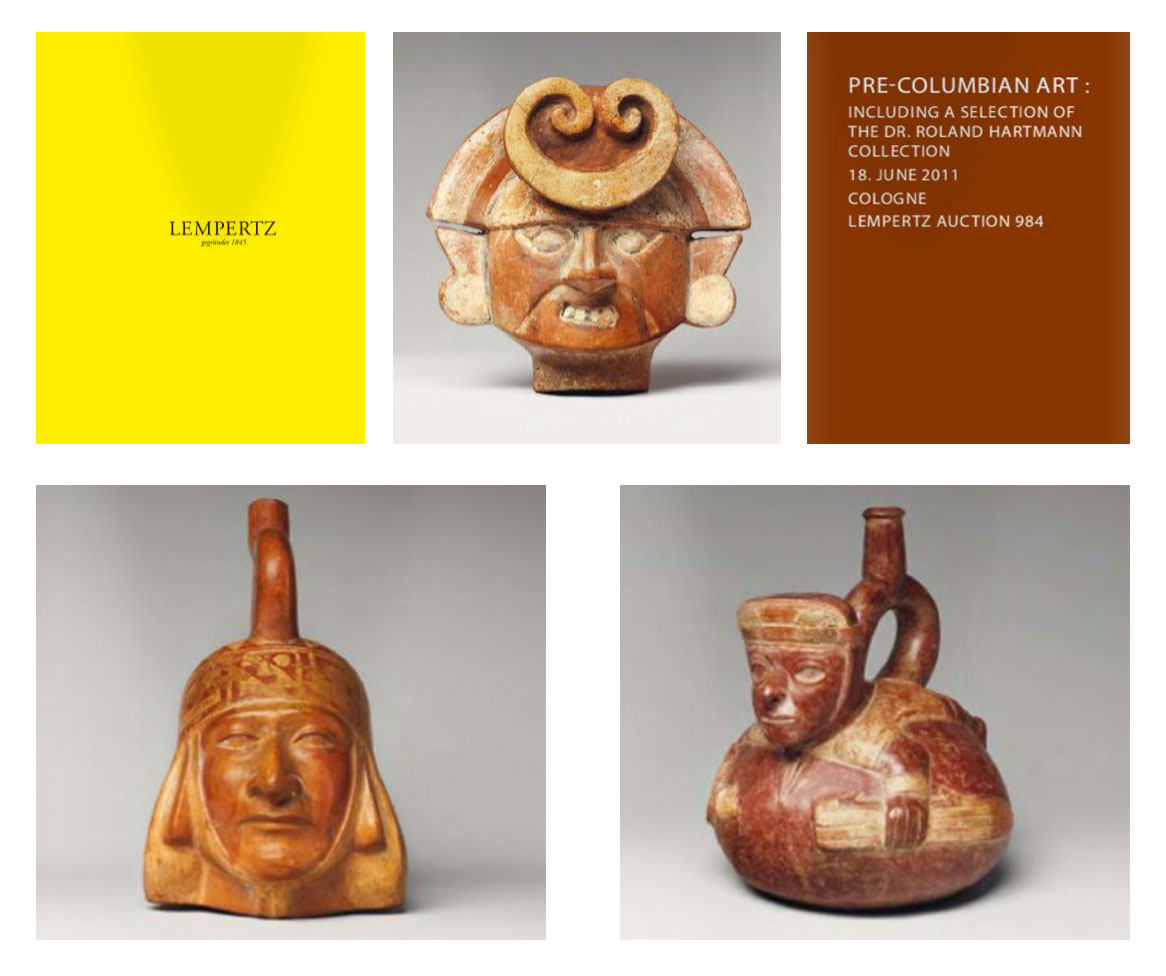

In September 2010, the Brussels branch of the Lempertz Auction House (the oldest in Germany and one of the most prestigious in Europe) announced the sale of a lot which triggered alerts in seven Latin American embassies accredited in Bellgium. The catalog was filled with Pre-Columbian pieces that Peru, Costa Rica, Guatemala, Mexico, Colombia, Ecuador and Bolivia recognized as part of their cultural heritage. Once these countries’ agents exhausted all Interpol and local police procedures, they requested an emergency meeting with the Belgian Foreign Ministry. They were expecting a tense meeting, as had been the case months earlier due to another auction. But the minister who greeted them had reassuring news: Belgium had just ratified the UNESCO 1970 Convention that seeks to control the import, export and trafficking of cultural property, and it was determined to honor it. The only problem was that every country had to present previously documented evidence that the pieces belonged to them, that they had been stolen, and, above all, that there was a judicial case requesting their return. All of this happened only three days before the sale.

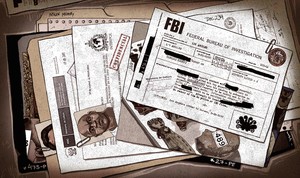

Significant arrangements began between the embassies and their Foreign Ministries following the meeting, in order to find the evidence needed. “It is impossible for the Belgian government to do anything to stop this auction without them,” the Guatemalan trade commissioner reported from Brussels, according to documents from the case, which are coming to light for the first time as part of the Stolen Memory Project: a journalistic endeavor that has comprised the revision of judicial records, theft alerts, technical reports, secret reports, and interviews in six countries, to expose the transnational mechanisms of the trafficking of cultural heritage in Latin America.

The documents were obtained and analyzed under the initiative of OjoPúblico, through a journalistic alliance created between teams from La Nación (Costa Rica) Plaza Pública (Guatemala) Animal Político (México) and Chequeado (Argentina).

One of these reports shows that, the same day the meeting of Latin American diplomats at the Belgian Foreign Ministry took place, a Lempertz’s spokesperson reached out to explain the house’s position. “He assured us that Lempertz is respectful of the law, and that before every auction, they make sure the pieces for sale have not been stolen,” the Central American diplomat informed. The spokesperson said that the proceedings would include sending the police a list of objects to be auctioned, and that the owners would be asked to sign an affidavit on the legality of their origin. The format of the document—reviewed for this investigation—is only half a page long, with three questions based on the word of the signatory. No more documented proof is required, other than an attached list of artifacts confirmed for the sale.

In spite of the efforts, none of the embassies were able to demonstrate the illicit origin of the pieces in a timely manner. The Belgian Foreign Ministry declared itself not competent to intervene on the case. The auction carried through on September 11, 2010.

It was, at least, the second effort in one year of various Latin American countries to stop selling the region’s cultural heritage, according to the reports examined. The embassies of Peru, Mexico, Ecuador and Bolivia had complained about another auction, also by the Lempertz House, eight months earlier. It announced Pre-Columbian pieces coming from “a private European museum.” The lot contained pieces from, among others, the Chavín, Tlatilco, Tumaco and Tiahuanaco cultures. “Many of the objects in the auction catalog belong to the Red List of Latin American Cultural Objects at Risk by the International Council of Museums (ICOM),” warned the letter sent by all four embassies to the Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs. The effort would fail for the same reason.

Both incidents uncover the structures hiding a global market for Latin American looted artifacts. Between 2008 and 2016 alone, the main auction houses in the United States and Europe put over 7 thousand objects belonging to the archaeological heritage of Peru for sale. In a similar time lapse—between 2010 and 2016—Costa Rican authorities detected the selling of relics from its own past in at least 23 auctions, and Guatemalan authorities did so too in 26 occasions, according to official reports obtained for this investigation in each country. The volume of Latin American pieces sold to collectors from the main capital cities in the world is even larger than the 4,907 cultural objects Interpol is currently searching for, as stolen throughout South America, Central America, and Mexico.

This is what one would call a lost museum (*).

This panorama—reconstructed with documents, databases, and direct sources—sheds light to incidents throughout the Americas. It also highlights the trail that links the countries with greater cultural heritage in the Americas to the epicenters of the international antique market; these epicenters functioning as layovers for artifacts in transit to some of the most important academic institutions and research centers in the world.

THE TRAFFICKING ROUTES

At the beginning of July 2014, the Interpol office in Lima sent message N°6608 to the organization’s branch in San José, Costa Rica. It was marked ‘Urgent’. Agents in Lima reported that a “possible trafficking network might exist for Peruvian cultural artifacts exiting our territory illicitly and reaching yours, to later be transferred to the United States of America.” The alert came from information obtained by the Peruvian Ministry of Culture and gave precise details about the stolen pieces, the people involved and their whereabouts. The message requested the seizing of two Peruvian-American citizens by the names Juan and Ingrid Bocanegra, owners of a store in La Paco shopping center in the exclusive San Rafael de Escazú, a place of luxurious hotels, condominiums and corporate buildings in the Costa Rican capital. It is presumed that a group of valuable works of art sought out from Lima was being kept there.

The lot consisted of about forty paintings among which were nine pieces from the Cuzco School (the most famous colonial art movement of the Andes) with frames of mahogany and cedar wood covered in gold leaf. The group also included “many more rolled-up oil paintings,” the report continued. The paintings could not have exited regularly, since they would have required a ‘Certificate of exportation of artifacts non-belonging to the cultural heritage,’ issued by the Peruvian Ministry of Culture. In the previous seven years, the Ministry had only granted 11 certificates of that nature with Costa Rica as their destination. None of them coincided with the pieces under suspicion. According to the intelligence analysis, the cargo was going to be sent to three different addresses in Washington, Miami and Indianapolis. One of those paintings was a portrait of Our Lady of Mercy, Patroness of Prisoners.

According to San José immigration records, Juan and Ingrid Bocanegra—79 and 73 years old—have visited Costa Rica indistinctively about ten times in the last two years. They tend to identify themselves with their Peruvian and their U.S. passports. The last time Juan Bocanegra entered the country was June 29 of last year. He left almost a month later.

The Costa Rican route of global trafficking of cultural heritage was confirmed with another episode that same year, when customs authorities in Washington seized a suspicious package sent by express mail from San José. It was a cardboard tube that supposedly contained one document valued at just one dollar. When the police inspected its content, they found a harlequin painted over paper in gouache technique. It had the signature of Pablo Picasso. There was a document of authenticity in the same tube confirming its real value: over $70,000.

Discreet arrangements were made between authorities of both countries in order to find the trafficker who had sent the package. When the Costa Rican police raided the condominium indicated in the return address, they only found a retired judicial worker. They had stolen his identity. The Picasso painting remains in Washington, confiscated in customs. Nobody has turned up to claim it.

“Central America’s borders are very permeable,” says Monserrat Martell, a specialist at Unesco’s Culture program in San José. “There is a lot of corruption at the airports, in customs. As much as we educate the personnel, the pieces will never be detected as long as corruption is endemic,” she points out.

Costa Rica is one of the Latin American countries with the least amount of stolen cultural artifacts reported to Interpol: only twenty. They are mostly paintings of different time periods, which, paradoxically, are not protected by the local heritage laws. This norm only considers the protection of objects of Pre-Columbian origin. Only two pieces of this sort are being searched for through an international warrant from Costa Rica: a metate made of stone and a ceramic pot from the Ganacaste province, one of the most important centers of Pre-Hispanic cultures in Central America. This is despite the fact that San José authorities detected about 214 Pre-Columbian objects to be auctioned in houses in Europe and the United States in the last few years. The National Museum of Costa Rica was not successful in claiming them because officials were unable to demonstrate the objects’ origins through documentation.

The paradox of this case is the fact that the person considered to be one of the largest traffickers of Pre-Hispanic heritage in the history of Latin America is a man born in Costa Rica. His name is Leonardo Patterson and he has taken refuge in Germany. At his peak, he was wanted by the Peruvian, Guatemalan and Mexican authorities for the illegal selling of hundreds of archaeological pieces, from ceramic objects to pieces of incalculable value made of gold. If he was never sentenced for this crime, it was not for lack of evidence, as part of this investigation shows. Patterson’s example is a testament to the fact that it is easier to catch a drug lord than a presumed art trafficker in Latin America.

CRIMINAL TIES

By the end of November 2015, a police operation aimed at capturing a drug lord alerted Guatemalan authorities about the new ties between art theft and other circles of organized crime. The public prosecution had ordered the capture of a man by the name of Raúl Arturo Contreras Chávez, age 43, who had a pending extradition warrant from the United States. Contreras, a robust man of harsh expression, was being investigated by the Department of the Treasury as a member of a network sending cocaine to the United States since 2004. According to the file at the Miami district attorney’s office—reviewed for the Stolen Memory project—the organization consisted of fifteen people. Among those captured were four Lebanese and several Colombians. The day he was captured, Contreras was in a half-empty house west of Guatemala City. There were no drugs in the residence, but he did keep many works of art hidden in furniture.

The police counted 27 pieces that day, including 12 colonial paintings and 10 religious figurines. Some images still carried the original gold leaf frame that they had at the moment they were stolen. The team of experts from the Department of Prevention and Control of Illicit Trafficking of Cultural Property—an office consisting of three employees at the Ministry of Culture of Guatemala—determined the origin of the pieces: 25, almost all of them came from a robbery at the Foundation for the Fine Arts and Culture (Funba) in Antigua Guatemala, by an armed criminal group that took thousands of silver objects and ancient paintings six months earlier. The other two pieces appearing in the drug lord’s capture had been reported as stolen by a museum in Honduras. The public prosecution did not establish if Contreras had participated in the planning of these robberies. Whatever happened to the other 289 pieces that remain missing is also unknown.

A possible link remains in the case of the seven paintings of “The Passion of the Christ” that were snatched from a temple by another armed group one year before the Funba robbery. During the investigation, the public prosecution and the Ministry of Culture of Guatemala obtained the version that the robbery had been ordered by a very powerful drug lord. An informant even gave evidence that the pieces had followed a reversed path all the way to Honduras. At some point, however, the informant disappeared and the possibility of getting those pieces back—which are part of the 333 artifacts searched for by Interpol throughout the world as part of the stolen cultural heritage of Guatemala—disappeared along with him.

Central American authorities have mixed ideas about the connection between drug trafficking and the trafficking of cultural heritage. “Since the drug lords don’t know the value of these pieces, they pay what they are asked to pay,” says Eduardo Hermández of the Ministry of Culture of Guatemala. On the contrary, cultural heritage in Costa Rica is considered an alibi for other illicit business. “They buy art and antiques because it helps them launder their money and legalize it acquiring desirable pieces that, once clean, can be put up on the international market,” explains Monserrat Martel, a Unesco specialist in San José.

The connection has been well documented in a case that links Colombia and Brazil.

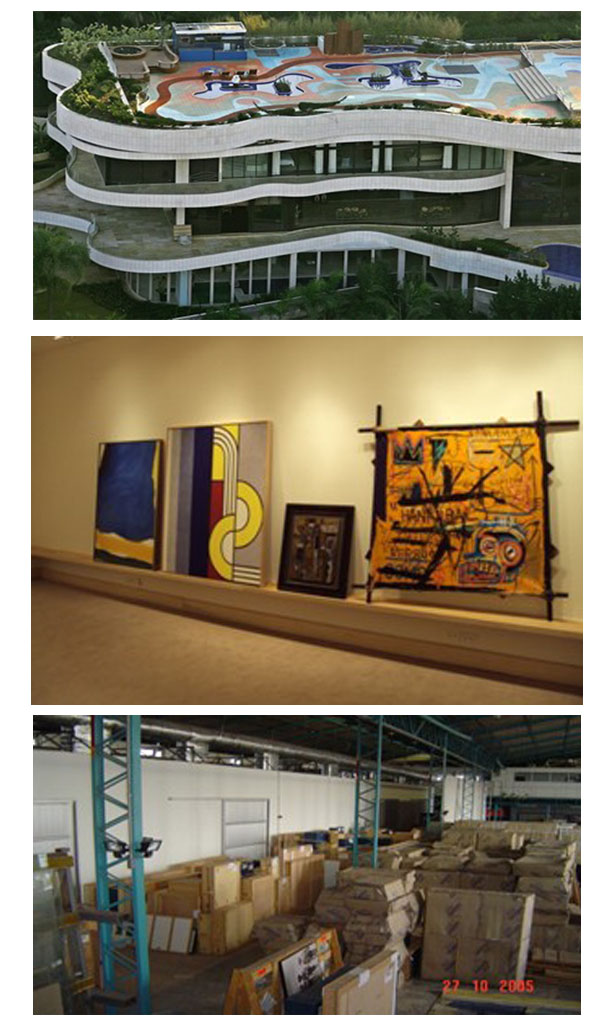

In August of 2007, an operation involving police forces from six different countries permitted the capture of Juan Carlos Ramírez Abadía in Sao Paulo, a Colombian drug lord who had an extradition warrant from the United States for exporting cocaine, as well as for the murder of fifteen people. Ramírez Abadía was a Cali Cartel leader, known for his violent personality and eccentric taste. He had built a complex weave of front companies and properties in which his two brothers participated, and, according to his affidavit, so did a few Spaniards. “It caught my eye that the drug lords had so many art pieces,” judge Fausto Martin de Sanctis recalls from his office in Sao Paulo. He saw the case and established that all of Ramírez Abadía’s property should be considered a product of his criminal activity. That included fifteen Brazilian paintings and artistic engravings valued at 4 million dollars, which were sent to the city’s Museum of Contemporary Art for temporary custody.

De Sanctis, author of the book “Money Laundering Through Art,” is a judge famous for investigations that have sent to prison criminals involved in organized crime as well as members of the Brazilian business elite. One of these cases involved Brazilian banker Edemar Cid Ferreira, who suspiciously amassed over a thousand works of art. “He wasn’t a connoisseur, he didn’t have a reputation in the art market, but he began to buy and buy at impossible rates,” the judge says. In 2006, Ferreira was sentenced to prison time for financial and money laundering crimes. The seizure of his art pieces required the participation of several security agencies from four different countries.

The complexity of the cases of money laundering through art and other variables, motivated judge De Sanctis to develop a proceeding called “anticipated selling of property,” which allows the selling of the defendant's property even before sentencing. “If in the end, the defendant is absolved, the money is given back to him. If he is convicted, the money goes to a government account,” the judge explains. This procedure allowed for the auction of drug lord Juan Carlos Ramírez Abadía’s property. It also allowed for the seizure of over 200 art pieces as part of the investigation of Operation Car Wash, one of Latin America’s biggest corruption scandals in recent times.

Others implicated in trafficking of cultural heritage, as linked to the corruption of the region, have had different fates. The most evident case is Mateo Goretti, an Italian political scientist who has been investigated by Argentine authorities for presumably laundering assets, and for aggravated concealment in a case of theft of cultural property. In April 2012, Interpol investigated Goretti’s house, as requested by the prosecution, to look for evidence. There, the agents confiscated 58 archeological pieces. Their heritage status should not have been unknown to Goretti, an expert in Pre-Hispanic art with many books published on the subject. Experts confirmed that the pieces had been part of a collection at a museum in the province of Córdoba, four years earlier. The political scientist claims to have freed himself from the lawsuit, but a case revision, which will be published as part of this investigation, shows that this is not true.

ANTIQUES DEALERS AND MUSEUMS

One September morning in 2015, the Peruvian ambassador in Buenos Aires, along a group of staffers, arrived at a warehouse crammed with boxes filled with cultural artifacts confiscated by the police. He was welcomed by government officials of Argentina and specialists from the National Institute of Latin American Anthropology and Thought (INALP), who had been in charge of cataloguing a lot of 4,150 pieces. The lot included pieces ranging from ceramic pots and musical instruments made out of bones, to a long, Pre-Columbian fabric of brown and blue stripes that Peruvian diplomats looked at with surprise, like seeing the shroud of a saint. They were actually pieces of a treasure that would confirm the Lima-Buenos Aires axis as one of the most important routes in the trafficking of cultural property in Latin America. Pieces belonging to Ecuadorian cultural heritage remained in the same facility.

The objects were evidence confiscated from Néstor Janeir, an antique dealer from Argentina’s capital who does not appear in international trafficking lists, but against whom judicial cases in Lima and Buenos Aires were opened for presumed trafficking of cultural heritage. The volume and the historical value of the returned pieces—which were packed into over fifty cardboard boxes—make this the largest recovery of illicitly exported artifacts in the history of Peru, and one of the largest in the continent.

The Janeir case is not the only evidence of the illicit trajectory that involves the antique dealers of Buenos Aires. Peruvian authorities maintain an open investigation, initiated in 2012, when a bibliographical jewel stolen from the National Library in Lima was found in a Washington library belonging to Harvard University. It was a valuable religious manuscript from the 18th century, written in Quechua. There was no news about the loss of the manuscript until a French academic by the name Isabel Yaya found it, while checking documents in Dumbarton Oaks, a research center specialized in byzantine studies and the Pre-Columbian period. Dumbarton Oaks is famous for its collection of rare books, with over ten thousand volumes.

Yaya informed one of her colleagues in Paris, Cesar Itier, about the finding. Itier, an expert in the Quechua language from Colonial times, knows these materials to perfection. He immediately recognized the book: he had studied it in Lima 10 years earlier, even keeping a photocopy of it for his personal archives. With that image as proof, the academic immediately alerted the Washington Library and the Lima authorities. It was found that Dumbarton Oaks had bought the copy from an antique dealer in Argentina’s capital, its provider of rare materials for almost twenty years. The antique dealer had put the document up for sale in his 2011 catalogue for $6,500.

The Lost Manuscript. A short documentary on the traffic of ancient books from Latin America to USA.

To prevent getting involved in an international scandal related to the buying of stolen cultural property, Dumbarton Oaks—which requested a questionnaire at the beginning of this investigation to give its version of the story but never answered it—opted to undo the purchase and requested a refund of its money to the antique dealer. The bookseller returned the manuscript to Lima without charge, under the condition that his name would remain confidential. In Peru, the return of the manuscript allowed for the identification of the circuit of traffic inside the National Library. In Argentina, however, the case has not been investigated to this day.

The trail of the cultural looting of Latin America does not only go from the poor South to the rich North. At the beginning of October 2016, international attention focused again on the Central American axis, due to the seizing of two fragments of Mayan stelas that were in exhibition at a private museum in El Salvador’s capital, and have been reported stolen in Guatemala since 2013. The pieces come from two Mayan archeological sites looted back in the nineties. Traffickers mutilated them so that they could steal them. The pieces’ whereabouts were unknown until an Interpol officer managed to identify them at the museum of the Tesak Foundation; an international alert was set up shortly after. The family of Pablo Tesak, the late tycoon of the confectionery industry, sponsors the museum.

The case was the cause of an intense diplomatic dispute. Guatemala sent up to eight requests for restitution of the pieces in a three-year period, without any positive response, even though the Central American Convention for the Protection of Cultural Heritage forces the signing countries to lend each other technical and judicial assistance in cases like this. A judge put an end to over thirty months of tensions last October, but the dispute did not end there. Today, Guatemala demands other 287 archeological pieces that the Tesak Museum was to send to El Salvador from the United States a year earlier, as part of a repatriation of Salvadoran cultural heritage. They were actually Guatemalan archeological pieces. When detected that they lacked clear information about their origin, custom authorities in El Salvador retained such pieces.

“We have unofficial information that the pieces were in Los Angeles, California, when they were imported to El Salvador by the Tesak Foundation,” reports Eduardo Hernández, chief of the department of Prevention and Control of Illicit Trafficking of Cultural Property at the Ministry of Culture of Guatemala.

A piece stolen from a Mexican church ended up in a different city of the same state. The painting, “Adam and Eve are expelled from Paradise”, is an 18th century work bought by the San Diego Museum of Art from antique dealer Rodrigo Rivero Lake, a man of engaging personality who frequently raises suspicions in his country and in other places in Latin America.

There’s a reserved file at the Attorney General’s Office in Mexico that mentions Rivero Lake in the robbery of a historical piece, even though the authorities have declared the details as confidential. “There are people involved who have not been arrested to this day,” indicates a request for transparency made for the Stolen Memory project. In Peru, the antique dealer remains under suspicion since a repenting trafficker revealed conversations in which he and Lake apparently negotiated the purchase of some stolen pieces from a chapel in the Andes. None of the charges against the repenting trafficker have prospered, and Lake maintains his lifestyle with frequent appearances in the society pages of his country.

Is good taste an alibi for organized crime? The findings that the Stolen Memory investigation releases from today onwards expose the true beneficiaries of an international scheme that favors the trafficking of Latin American cultural heritage: diplomats who abuse their dignity, criminals with money to launder, politicians who find shelter in the loopholes of the law, presumed art detectives who benefit from tax havens, and merchants who save evidence in back rooms. The traces of their illicit activities were intangible, until the massive data analysis we present in this report. This is the first census of stolen, auctioned or repatriated cultural property in the region: over 50,000 pieces that should enter the criminal records of the least punished traffickers in the world.

____

Traducción: María Jesús Zevallos.

(*) A reference to the book "The Lost Museum", by the Puerto Rican journalist and writer Hector Feliciano, that reveals the looting of art organized by the Nazis in the mid-twentieth century.