Diplomats and collectors under suspicion in the trafficking of Latin American art

Many operators in the highly lucrative trafficking of Latin American cultural artifacts to the United States and Europe have been identified but few have been investigated and others have evaded justice because of loopholes in the law. The struggle against this crime has failed in various countries in the region. Proof of this is the freedom still enjoyed by almost all those accused of the largest cases of theft, export, trade and illegal possession of pieces of art discovered over the last two decades. Journalists from five countries visited prosecutors, immersed themselves in files and interviewed the accused to unearth and relate this history of impunity.

Translation: Alex Jefremov

The art and antiques store of the Uruguayan Néstor Janeir Aude, is located in the historic suburb of San Telmo in Buenos Aires, at the epicenter of the largest antiques market in Latin America. The serenity with which he serves the customers belies the fact that this same person is described in a voluminous legal file—unknown until now—as one the principal traffickers in archaeological and paleontological artifacts stolen from the Andean region. The same person from whom the government of Argentina confiscated four thousand Peruvian and Ecuadorian Pre-Columbian objects during two police operations at another antiques store he previously owned. The objects were returned to Lima in January 2016 following 14-year legal battle in the civil courts. Janeir, however, escaped the charges because they had lapsed in 2011. His new antiques business is situated in a colonial-style mansion with yellow walls in Calle Defensa, a street popular with tourists.

The man who attempted to hold on to the legacy of four countries becomes tense when asked about the process to which he was subjected over several years in the courts. “They came saying things like I was part of an Al Qaeda cell and today, whenever I travel, they put obstacles in my path at the airport. Even when I travel with my children. It recently happened even during a domestic trip”, he comments. His suspicions are increasing. Someone recently entered the store to ask if he was selling gold. Janeir is convinced that it was an undercover police officer.

The dealer, of Syrian descent, is not a member of the prestigious Association of Antique Dealers and Friends of San Telmo, nor is he well known in the circle of Latin American antique traders. But his information does appear on records of investigations into the trafficking of cultural assets kept by Interpol’s Buenos Aires office. His case led to an amendment of the Argentine Law on Protection of Archaeological and Paleontological Heritage in respect of those collectors who registered themselves after 2003. In the middle of 2015, it led to a legal finding about the return of stolen cultural artifacts that was without precedent in Latin America: a Buenos Aires court ordered the repatriation to Peru, Ecuador, Bolivia and Colombia of thousands of archaeological artifacts that had been impounded, reasoning that although the crime committed by the antiques dealer could no longer be prosecuted, the state ought to cooperate with other countries in the region to protect their cultural heritage.

The finding against Néstor Janeir Aude reads, “If our Government expects its claims to be heard by other nations in whose territory are found goods and artifacts that it considers to constitute its cultural heritage, it must necessarily lend and provide assistance to those [nations] when they request it. To do otherwise would be to turn the rights and obligations which derive from the law into a dead letter”.

The case dates back to 4 November 2001, when the responsible official of the Cultural Heritage Directorate of the Argentinan Aeronautical Police reported the continuous movement of suspicious merchandise that was arriving at Ezeiza International Airport from different Latin American countries, destined for the antiques stores in the center of Buenos Aires. Specifically, to businesses in the Galería del Sol, at number 680 Calle Florida, where the antiques house of Néstor Janeir Aude originally operated. The police then began an intelligence operation which included telephone intercepts, entry of premises and expert reports, that confirmed their suspicions: in Janeir´s business, as well of those of the antiques traders Carlos Languasco, Carlos Osona, Enrique Álvarez and José Arias, more than 15 thousand original archaeological artifacts, which had entered Argentina in parcels labeled “objects of little commercial value”, were being sold.

After interrogating Janeir´s computer, the police discovered that the antique dealer had used email to coordinate the requests of clients from all over the world and to identify the characteristics of the items sent by commercial flights from Andean countries to his gallery in Buenos Aires. “They were sent personally or through intermediaries to the final buyers, who had previously made a deposit in dollars to his bank account in Citibank”, reads a document on file number 42282 of the 3rd Federal Criminal and Correctional National Court in Buenos Aires.

Although Néstor Janeir Aude was born in Uruguay, he has Argentinian citizenship and is married to Myrna Garazatúa Diaz, a Peruvian. Following the Buenos Aires police report in 2001, the 54th Provincial Penal Prosecutor in Lima opened an investigation into both of them—and three other family members—for the crime of extraction of objects of Peruvian cultural heritage. Thousands of original ceramics, from the Mochica, Chavín, Cupisnique, Chancay and Inca culture, had been found during the police entry of his gallery. However, the Peruvian process was archived in 2005 due to lack of evidence. In Argentina on the other hand, the police found new evidence against Janeir two years later, when they entered his gallery for a second time. The dealer had additional unrecorded archaeological assets, despite the fact that by then he had registered himself as a collector.

In 2009, the Peruvian Ambassador in Argentina was recognized as a complainant in the legal process against Néstor Janeir and another four antiques dealers for illegal possession of archaeological and palentological artifacts. A battle began for the repatriation of 3,898 items of Peruvian cultural heritage. This same year, the same 3rd Federal Criminal and Correctional National Court seized all the confiscated goods but declared the process lapsed. Nevertheless, the antique dealers appealed the sentence on the grounds that, if the case had been archived, the objects belonged to them and should be returned. The legal representative of the Peruvian Embassy in Argentina, Emilio Itzcovich Griot, also appealed the court´s decision, considering that an investigation was being stopped of a case that showed all the hallmarks of an international network of traffickers in Latin American archaeological artifacts. “Because of the significant number and the quality of the goods impounded, the dealers could only have obtained them via persons who had extracted them from their sites of origin, or in an otherwise illegitimate manner”, the lawyer stated in the appeal document.

The fact that Argentine Law on Protection of Archaeological and Paleontological Heritage included a jail sentence of between only two months and two years for cultural heritage traffickers, compounded the problem created by the lapse of the cases against Néstor Janeir and the other dealers due to the length of time that had elapsed. In November 2011, the court ratified extinction of the criminal proceedings and ordered that the more than four thousand archaeological items be returned to the affected countries. Only Néstor Janeir tried to recover the artifacts, through successive appeals in 2012 and 2013.

In June 2015, the 3rd Federal Criminal and Correctional National Court ordered final seizure of the archaeological and paleontological items and ordered the National Institute of Anthropology and Latin American Thought, their custodian over several years, to commence return to the countries of origin. The finding was sufficiently conclusive as to thwart Néstor Janeir´s hopes of recovering the objects and to clarify his degree of responsibility. The finding states: “Whilst the prescription of the criminal case with respect to the persons accused has been declared, the contravention of the law occurred from the moment in which it was determined that the objects taken were archaeological and paleontological, and of scientific interest”.

And so it was, that a lot consisting of more than three thousand items belonging to Peru and 439 to Ecuador, were returned from Argentina in January 2016 through diplomatic channels.

Néstor Janeir was able to continue selling antiques in his San Telmo store, since no further archaeological items like those seized in 2001 and 2007 had been detected, according to Marcelo El Haibe, director of Interpol´s Cultural Heritage Protection Division in Argentina. But even now, the antique dealer considers himself to have been persecuted by the police and to be a victim of larceny. “The Argentinian Government delivered the objects to Peru and Ecuador but I doubt they have delivered all of them”, he said in an interview in Buenos Aires for the Stolen Memories investigation. At an exposition that took place in the National Museum between June and September in Lima, the Ministry of Culture displayed various ceramics, bone remains and Pre-Hispanic textiles recovered from Néstor Janeir´s gallery.

Blanca Alva Guerrero, Director General of the Ministry´s Heritage Defender, has referred to the Janeir Aude case as “one of the most important for our country in terms of recovery”. Paradoxically, Magda Atto, the only Peruvian investigator examining cases of trafficking in cultural heritage, has no report of the case, or did not have one when she was approached as part of our investigation. Those who do seem to be be aware of the case include the Head of the Office of International Cooperation and Extradition, Alonso Peña, and his assisting lawyer, who showed as a dossier with yellow pages in their small office located on the ninth floor of the main building of the Public Ministry of Peru. Curiously, according to the information held by these officials, Néstor Janeir is a prisoner in an Argentinian jail.

THE PATTERSON FILE

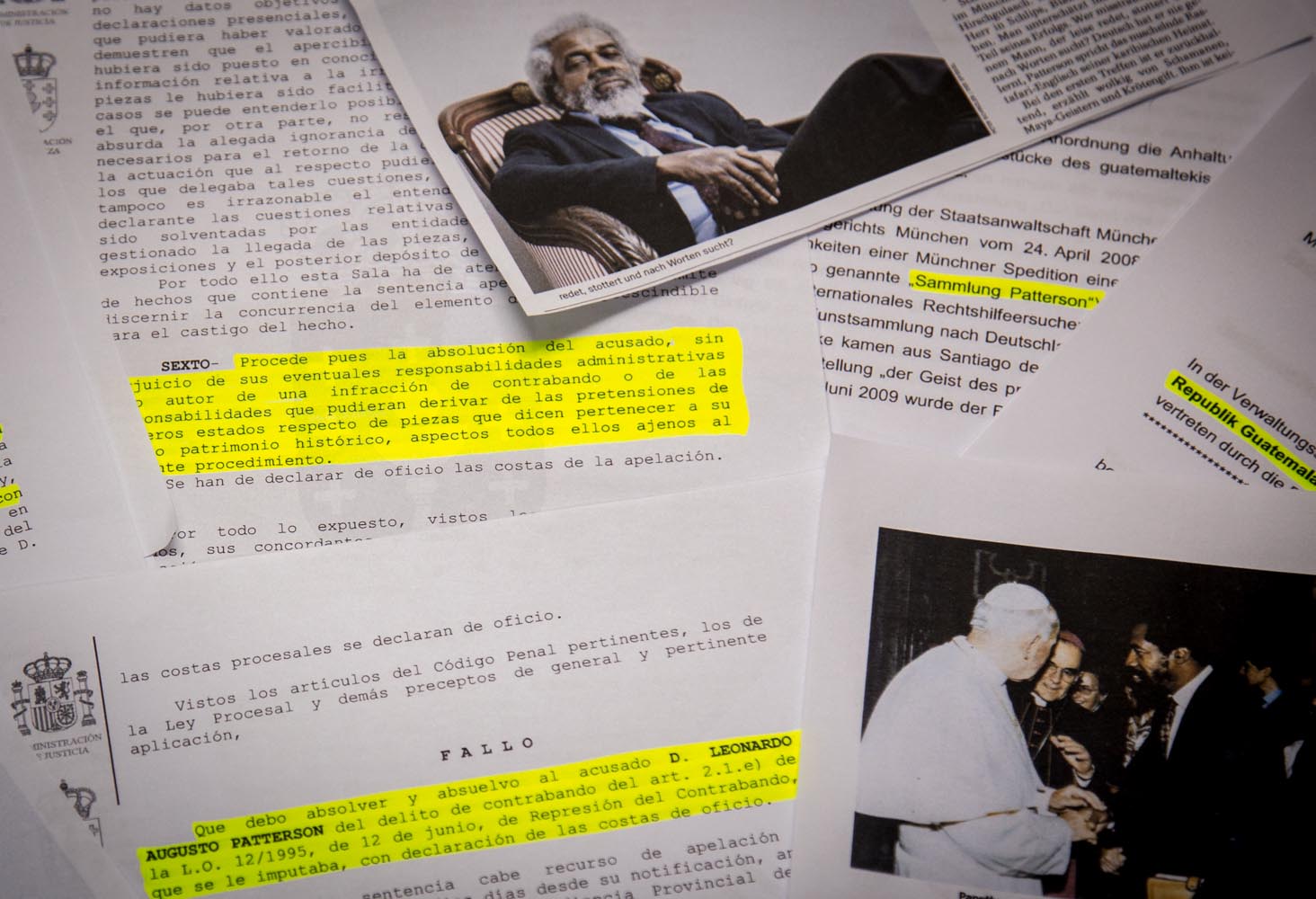

Until now, it was thought that former Costa Rican diplomat Leonardo Patterson had lost control of his famous collection of more than one thousand Pre-Hispanic archaeological items, after he brought it into Germany in 2008, fleeing charges of trafficking the cultural artifacts of six countries. However, the collector and art dealer with one of the longest criminal records, which includes three detentions and five sentences for different offenses, can avail himself at any time of his Pre-Columbian treasure: the items are not in the custody of any authority, but are instead stored in a private warehouse in Munich. In November 2015, a Bavarian civil court found him guilty of possession and illegal export of cultural assets, but only in respect of two wooden Olmec heads that were confiscated from him after an exhibition and must now be returned to Mexico. Patterson is not obliged to respond to German justice for the remainder of the stolen objects that for more than a decade Peru, Guatemala, Costa Rica, Colombia and Ecuador have also claimed from him. Notwithstanding this, his defense has appealed the ruling and awaits a new verdict.

At 74 years of age, Leonardo Patterson lives on probation in an apartment in Munich without the luxuries of his golden age. Days after the civil court´s first ruling, he received a second conviction, this time from a criminal court, which gave him a suspended sentence of one year and three months prison and a fine of 36 thousand euros for selling a fake Olmec bust to a German citizen as if it were an authentic archaeological piece. The item in question was also part of his private collection of Pre-Hispanic art displayed for the only time in Santiago de Compostela, Spain, in 1996, an exhibition that led to an Interpol alert about the illicit origin of his collection, triggering criminal charges in five countries from 2004.

However, twelve years after this international scandal erupted, Mexico is the only one of the affected countries that has persisted with diplomatic overtures and legal action in Germany, in its case to recover 691 authentic Mayan archaeological artifacts which were looted from its territory and identified in Patterson´s collection. Mexico was also the only country which paid the 90 thousand euros that the German authorities demanded from each of the claimant states as part of the costs of the expert investigation and the storage of the objects in 2010. The Mexican General Prosecutor and the National Institute of Anthropology and History now have the lawyer Robert Kugler, as their representative accredited in Munich to evaluate a new claim in the civil courts in respect of stolen assets. “An important step has been taken in the process of investigating the origin of many of the objects illegally bought and sold over the years by Mr Patterson. A lot of work remains to be done”, says Kugler via telephone in an interview for this investigation about the two sentences imposed on Patterson by German justice.

The outstanding work is complex, the main reason being that under German Law on the Repatriation of Cultural Heritage, the principle of good faith applies to substantiate the ownership of a cultural artifact even where their acquisition was illicit. The norm also demands a number of prerequisites which even the German Parliament considers excessive: one of which is that the affected state demonstrate that the item claimed was duly registered in a publicly available database of all cultural artifacts and, above all, that this was accessible to German citizens. Another of the law´s conditions is that only those objects which entered German territory after 2007 may be returned, because Germany only recently ratified the UNESCO Convention for the Protection of World Cultural Heritage, 35 years after it came into force. It was based upon this legal framework that the Bavarian Supreme Administrative Litigation Court rejected the requests from Peru, Mexico, Guatemala, Costa Rica and Colombia for restitution of archaeological pieces in 2010, according to resolutions made public for the first time by in this report.

Leonardo Patterson’s life story is littered with investigations, detentions and light sentences from the time he started in the business of selling antiques in the United States. The patron for his rise into the upper echelons of this market was Everett Rassiga, a New York gallery owner famous for trafficking, who, during the seventies, was involved in the theft of the Mayan object, La Fachada de Placeres. Patterson, who never attended school, started work as a salesman in Rassiga´s gallery. There he began to build a circle of contacts and to gain notoriety as not just a collector of Pre-Hispanic objects, but also as a skilled art swindler. He was sentenced for fraud (Switzerland, 1975), for smuggling protected species (Dallas, 1984) and a swindle involving the sale of fake works attributed to Salvador Dalí (Basel, 1991). His curriculum vitae includes a term as Costa Rican Counselor to the United Nations in 1995, however this appears to have been the most fleeting position that he ever occupied: the Costa Rican government was forced to withdrawn him that same year after The New York Times revealed that Patterson had offered for sale several archaeological items stolen from Sotheby´s auction house.

Patterson´s name is also linked to the brutal murder in 1996 of the Peruvian collector Raúl Apesteguía. On the day of the crime, one of the most important pieces of Pre-Columbian art disappeared from the victim´s house in Lima: a headdress of Moche gold which represents a human head. In 2006 the piece was discovered at the residence of Patterson’s lawyer in London. Peruvian prosecutors however, never investigated the links to this still unpunished case.

In 2013, Peru and Guatemala presented extradition requests against Patterson while he was in Spain. In that year, a court in Santiago de Compostela was able to have him appear on charges of smuggling cultural property, generated by the illegal transfer of his collection to Germany when the allegations against him began. However, Patterson was acquitted, settled in Munich and the extradition requests became void. “Peru has no extradition treaty with Germany and for a request to proceed, the possession of cultural assets in private hands must be considered a crime. Germany does not consider it a crime”, states the Ministry of Culture´s Blanca Alva.

Unlike the other affected countries, Peru managed to recover 273 objects that it claimed from Leonardo Patterson while they were kept in a warehouse in Santiago de Compostela, because it was the first to discover the illegal origin of the collection and begin diplomatic negotiations with Spain for its repatriation in 2006. However, the return of four textiles is still outstanding (three painted cloths from the Chimú culture and one from the Nazca-Wari included among the pieces that were moved to Munich) and nine pieces of Pre-Hispanic goldsmithing that, whilst part of the 1996 exhibition catalogue, were not found in the warehouse. The Ministry of Culture sent four letters of request to Germany for recovery of the goods, but they were all rejected.

The judicial process in Lima was archived in 2013. The 45th Provincial Penal Prosecutor had requested five years prison for Leonardo Patterson for illegal trading in cultural objects, as well as civil damages of one million soles (just over 300 thousand dollars in today´s terms), but following the frustrated extradition request, the case stalled and the Public Ministry also ceased to investigate the network of suppliers of art objects in this country. One of the first tip-offs was the Peruvian Delia Podestá Cuadros, who was detained at Munich Airport with a Pre-Columbian artifact in 2001 and who—according to her own police statement—was going to deliver it to Patterson. She was included in the prosecutor´s charge against the former diplomat.

Guatemala claimed the return of 369 Mayan archaelogical pieces from Patterson´s collection, but has also desisted in its attempts to recover them. In August this year, the prosecutor of the case, Rolando Rodenas, said that he would seek the final archiving of the case given that the country had not met the requirements set by Germany. The main difficulty is that the objects claimed do not appear in any official register because they were taken from deposits that were yet to be formally explored. According to the file, the expert´s report about the Guatemalan archaeological pieces in Germany was only undertaken using photographs because the state did not allocate sufficient budget for an expert to travel to Munich. It also did not invest in lawyers.

Costa Rica, which on one occasion demanded that its former diplomat return 497 archaeological items which appeared in his private collection, also undertook an investigation lacking in resources. In 2009, the National Museum of Costa Rica sought access to the items in order to conduct an expert assessment, but was unable to afford the expenses that the German process required. The country only recovered two objects, a vase and stone grinding stone, left behind by Patterson in Spain. But these disappeared from the Costa Rican Embassy in Madrid in 2010.

The German Government offered Costa Rica the possibility being appointed legal custodian of Patterson´s collection, but only if it could provide a guarantee of several million euros. The Central American country was unable to do so. Although Leonardo Patterson is not well known in his native country, for those who are familiar with his name, it is synonymous with fraud. “Patterson made a business out of archeology and the falsification of objects. He linked himself politically with the ruling class in Costa Rica during all its governments. He had a gift for deceiving people. That is what makes one wonder how the [art] market works”, says Rocío Fernández, Director of the National Museum of Costa Rica. There is no current legal process open against Patterson in San José and the diplomatic channels with Germany for the recovery of Costa Rica´s heritage have not been reactivated.

The same occurred in the case of Ecuador, which claimed 121 cultural artifacts identified from photographs on a disk which Interpol provided in 2008. The Ecuadorian Ministry of Culture made no criminal complaint against Patterson and suspended the requests for return in 2010 after lodging a complaint with the German authorities for not providing access to certified copies of documents from the process against the collector in Munich. Colombia assigned its case to the Bogotá Crime Against Intellectual Property and Telecommunications Unit. It also suspended its claims several years ago.

The collection of Pre-Hispanic art may be the only thing of value now left to Leonardo Patterson. He has disposed of his polo horses, his Rolls Royce and properties in the United States and Europe in order to maintain himself in Munich, unemployed and in a lifestyle more appropriate to someone of his advanced age. He has fallen behind in payment of the fees of his lawyer, Peter Von Borch.

But even so, he appears, smiling and surrounded by Pre-Colombian figures, in photographs taken in his apartment for a report published in Der Spiegel magazine in May 2016. He confesses to the journalist Konstantin von Hammerstein, “all these objects of art came into my possession thanks to a network of collaborators who explored archaeological sites in different countries”. Leonardo Patterson declined to be interviewed for this investigation and did not respond to questions by email which we sent via his lawyer.

THE DIPLOMATIC COLLECTOR

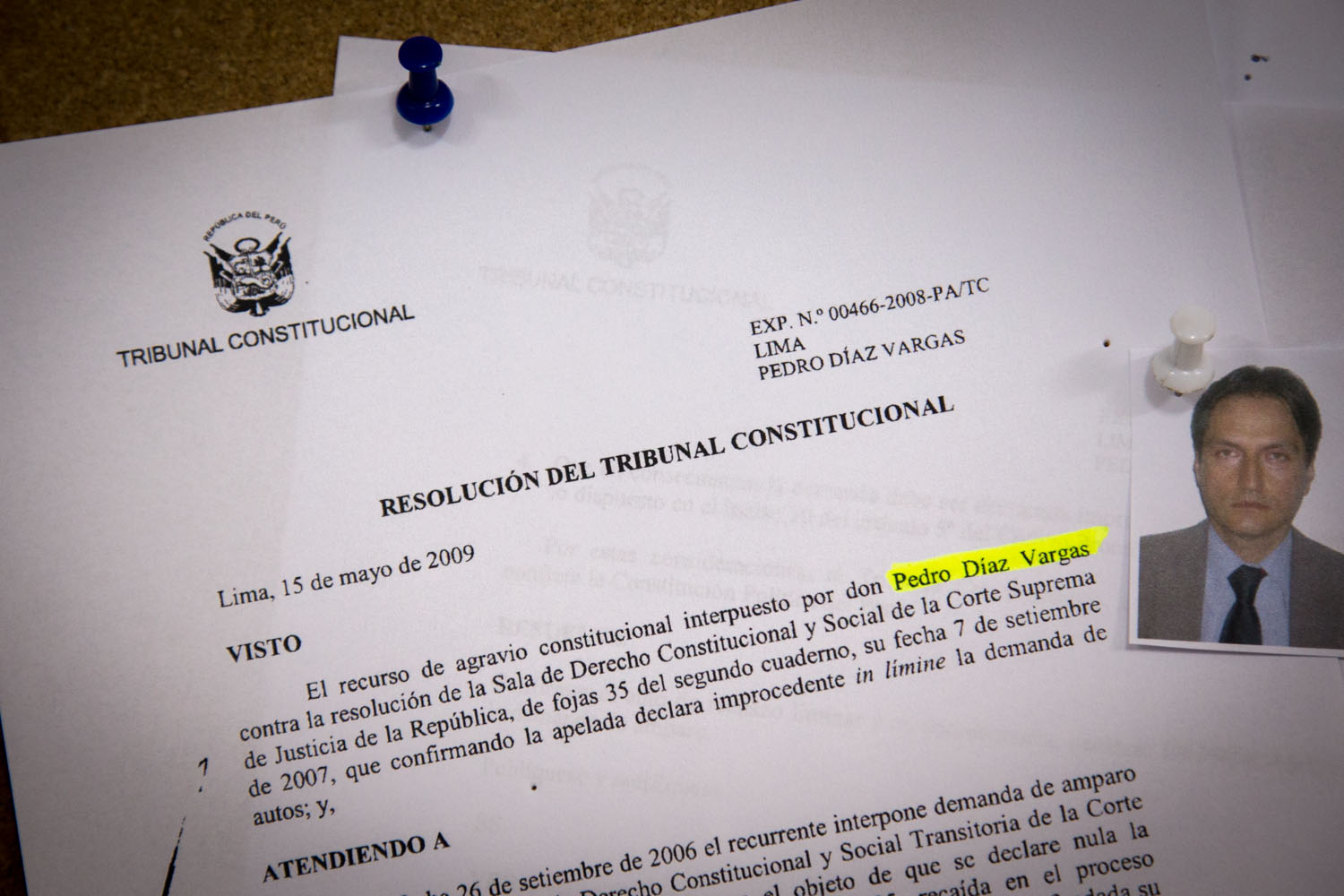

One afternoon in September 2000, Bolivian police discovered dozens of stolen colonial religious paintings in the apartment of Pedro Julio Díaz Vargas, then Peruvian cultural attaché. This generated an international complaint that even now causes disagreement between the authorities of both countries. The case provides key clues to the illicit market in religious art that operates in La Paz even though judicial deadlock prevented the identification of the criminal networks which supply it. While a judge in Lima determined almost ten years ago that there were insufficient grounds to investigate the diplomat involved and so archived the case, few know that another magistrate in La Paz in 2009 sentenced Pedro Díaz Vargas to nine years in prison for the reception or destruction of and damage to, cultural heritage. However, his lawyer, the former Bolivian Vice-Minister of Justice, appealed the sentence to the Constitutional Court, where, after two partial pronouncements, in 2013 it was annulled. Pedro Díaz Vargas is still a member of the Peruvian Association of Active Diplomatic Officers. He was most recently promoted in 2013. However, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs declined to provide information about his diplomatic career and its reception desk refused to receive a letter about the issue.

Pedro Díaz Vargas has been part of the diplomatic corp since 1994. After undertaking studies in London, the Ministry sent him to the Peruvian embassy in Bolivia in 1997, where he occupied the post of Cultural Secretary until the end of 2000. He was recalled from La Paz and suspended for one year because of the scandal about the stolen works of religious art. He was then named Peruvian consul in Ecuador and was promoted to First Secretary in 2013. Over the course of the last twelve years, he has never referred to his legal situation in Bolivia and by the close of this report had not responded to our request for an interview. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs also did not respond to our questions.

We did however review the Constitutional Court file and interviewed by telephone his lawyer, the former Vice-Minister of Justice Denise Mostajo Sotelo, who said that the process was annulled because it needed to be tried in Peru. “A finding by Bolivian justice would have had no legal status because international treaties establish that diplomats remain subject to the jurisdiction of their own countries even when the alleged crimes are committed overseas”, she said. In any case, since the Sixth Penal Court of Lima archived the compliant about trafficking of cultural objects in 2004, the lawyer believes that no judge in La Paz could have made a finding in respect of a case which was effectively closed.

Twelve canvasses of the Cusqueño School which had been reported as stolen in Peru were among the 205 works of colonial art found by Bolivian police in the home of Pedro Díaz Vargas. These were returned in 2002, thanks to the police report of the theft and a register of photographs of the works. However, the diplomat never explained when paintings such as the La Virgen de San Lázaro, Cristo Vejado, Mártires Cristianos and San Francisco Xavier were bought, nor how, nor by whom. He did, however, claim in interviews published in the El Comercio newspaper at the time, that he dedicated two thousand soles of his salary to the purchase of religious items, which, having been stolen from churches in the south of Peru, later appeared in the La Paz antiques market. “It was a way of recovering them so that they could then be returned to their place of origin”, he said. He was backed by the then Peruvian Ambassador in Bolivia, Harry Belevan, who said the following of Díaz Vargas: “He is a private collector registered in Peru and as Cultural Attache, part of his job is recovering cultural heritage”. Belevan later admitted however, that the peculiar way in which Díaz carried out his commission was never communicated to the Bolivian Foreign Affairs Ministry.

Since stolen Bolivian colonial paintings were also found in the apartment of Díaz Vargas, the Bolivian Ministry of Culture opened a judicial process against him in November 2000. The diplomat never presented himself before the judge. The Third Sentencing Judge of El Alto in the Judicial District of La Paz tried, convicted and sentenced him in contempt of court. In the 2014 book El rostro de la inseguridad en Bolivia (The Face of Insecurity in Bolivia), published by the Friedrich Ebert Foundation, Lupita Meneses Peña, National Director of Classification of Cultural Objects of Bolivia, writes “We verified the complete origin of all these objects and while the majority were not classified, 12 were colonial paintings of Peruvian cultural heritage and they were returned; another group of seven paintings were from churches in La Paz and Oruro”. Among them were the paintings San Jerónimo Penitente, La Entrega de Llaves a San Pedro and El Rostro de San Francisco de Paula, which were later delivered to museums in La Paz.

The historian Dominique Scobry Leacey, who the shared the apartment in La Paz with Pedro Díaz Vargas, was also tried as an accomplice in the case and sentenced to nine years jail. This French citizen, known to be an expert in colonial and Pre-Hispanic art, was considered a fugitive from justice in Bolivia until five years ago. Nevertheles, from 2007 to 2009 he worked in Peru as the Director of the Alliance Francaise in Piura and from 2011 until one year ago, held the same position at the institute´s headquarters in Lahore, Pakistan.

At the beginning of this century, another diplomat was caught up in an international scandal about the trafficking of cultural goods from Latin America to Europe. The Swede, Ulf Lewin, who today travels the world as an expert in Latin American cultures, was accused of having illegally exported hundreds of Pre-Hispanic pieces from Colombia, El Salvador, Bolivia, Guatemala and Peru, during his time as Swedish Ambassador in these countries. The case, which was revealed by the Stockholm television program Striptease in February 2000, was quickly closed that same year after the Swedish Ministry of Foreign Affairs prepared a report which concluded that there was no evidence against Lewin. However, none of the affected countries were consulted during the investigation that the report documented.

When the accusation arose, Ulf Lewin was approaching his penultimate year in the diplomatic corp, as Ambassador in Peru. The Fujimori regime had decorated him only four days earlier with the Orden del Sol (Order of the Sun) at the Gran Cruz (Great Cross) level, for the work he had performed in this country from 1995. The allegation that for years he had used the diplomatic bag to transfer cultural objects, left it mute. Lewin returned to his country shortly afterward, without clarifying the origin of the more than two hundred objects that he had acquired, some of which he donated to the Gothenburg Ethnographic Museum. Between 2000 and 2002, Lewin was Ambassador in the Baltic States, and the following year he retired to undertake a masters in anthropology at the University of Uppsala. Since then, he has become known for books he has written and conferences he has given about the Swedes in Central America. He did not respond to an email requesting an interview for this report.

The complaint against Ulf Lewin made by two reporters and an archaeologist from the University of Gothemburg was never brought to trial in Sweden. The country does not consider the possession of illegally obtained cultural objects to be a crime and has therefore not signed the UNESCO convention and the Unidroit principles regarding trafficking in stolen culture heritage. The report by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs exonerating Lewin was sufficient for the 9th Callao Specialist Penal High Court to archive the investigation against him. The decision was ratified by a superior court in 2001.

Subsequently, the government of President Alejandro Toledo restored the Orden del Sol decoration, which the transitional regime of Valentin Paniagua had stripped from Lewin. The drastic resolution had been issued by the then Minister of Foreign Affairs, Javier Pérez de Cuellar, but was overturned by his successor Diego García Sayán, who noted: “No competent authority in Peru or in the Kingdom of Sweden has found that Mr Ulf Lewin removed, in violation of Peruvian and international norms, objects of our historical and cultural heritage”.

Mariana Mould de Pease, a historian, closely followed the case. She maintains that there was no proper investigation in Sweden because Peruvian specialists were precluded from participating and Lewin did not make public the list of items in his collection nor did he prove the origin of those he donated to the ethnographic museum. The latter included ceramics and other Mochica and Vicus objects. “I have copies of the registry cards for these pieces and I will make them available to any authority, institution or person who wishes to examine the issue”, said Mould, fourteen years ago. But no authority has ever requested them.

The clues about Lewin which lead to the Swedish television report were found in the Gothenburg museum, where the archaeologist Staffan Lundén came across original Pre-Colombian objects in one of the galleries. They attracted his attention and he inquired about their origin. The museum informed him that they had been part of Ulf Lewin´s private collection. Lewin had been President of the Association of Friends of the Museum between 1994 and 1996. The Stockholm press also revealed letters to friends of the former ambassador in which he says, “I had improved my Nazca, Chavín and Virú collection”.

Colombia complained that Ulf Lewin took pieces from the Tumaco culture, but never formalized any legal process against him.

Lewin has never returned any of the objects from his private collection.

THE ADVISER´S MUSEUM

Since police found one of Argentina´s most important archaeological collections, stolen from the Ambato Museum in Córdoba, in home of the Italian political scientist Matteo Goretti Comolli, former adviser to President Mauricio Macri, he has denied responsibility on the grounds that he did not steal the items, but instead acquired them in good faith. Nevertheless, last August, the Córdoba Federal Appeals Chamber determined there to be a number of facts to investigate and ordered the reopening of the investigation against him for cover-up of theft and trafficking of archaeological items in Argentina. In its finding, the court annulled an earlier resolution that archived the complaint and requested that the judge which had dictated this be removed from the case.

The Ambato Museum´s Rosso Collection, which contains more than 700 archaeological artifacts from the Pre-Columbian culture at La Aguada, was stolen one night towards the end of February 2008. Four years later, 58 of the missing pieces—the majority ceramic vessels—were found in one of four properties in Buenos Aires belonging to Matteo Goretti, an art collector better known for being president of Fundación Pensara—a think tank of the governing party in Argentina—and for an allegation of money laundering.

Matteo Goretti agreed to respond to questions for this investigation sent by email and was asked: “How did the pieces turn up in your house?” He replied, “All the items in my collection were bought or donated. I was the first large collector to register a collection. I did so as soon as it was possible to do so, that is to say, when the registry was first implemented in Argentina. In terms of the set of items in question, Law 2543 requires the owner to register them. If one does so, according to the law they were obtained in good faith. It is not necessary (and the law does not require) that the documentation of the purchase or donation be presented”.

Nevertheless, the Argentine prosecutor claims that in reality Mateo Goretti made only a partial registry and did so not before the proper authority, but instead before the Government of the City of Buenos Aries, with which he had a relationship as an adviser in 2006. The President of the Institute of Anthropology and Latin American Thought has come to the same conclusion. Diana Rolandi explained that Goretti registered 800 pieces from his private collection in 2007 and registered nothing subsequently. “It is false that he bought the [Ambato Musuem] pieces in good faith, because the process for buying and selling requires the individual to register them. This is not what he did”, she declared.

Commissioner Marcelo El Haibe, head of the Department of Protection of Cultural Heritage of Interpol Argentina, has had Mateo Goretti identified for year as a collector linked to the trafficking of cultural items and describes him in this way: “He is another who believes that anything can be appropriated. He is a very intelligent person, adept at collecting archeology, someone who always tries to connect himself with power”.

The relationship of Goretti with archaeological items goes back much further than the Ambato case. In 2006, according to an official document from the Province of Salta, the former adviser to President Macri donated an Inca-period mummy to the Alta Montaña Archaeological Museum for exhibition. However, it was delivered in a poor state, despite the fact that he had presumably successfully subjected it to “diverse and complex conservation processes undertaken by a team of specialists” and the fact that his foundation (The Study Center of Applied Public Policies) had also edited a book on the subject. Goretti had already faced controversy two years earlier with the then Secretary of Culture, Torcuato Di Tella, when he tried to open a museum in San Telmo with 1,500 pieces of Pre-Colombian art, in contravention of the law. The confrontation stretched as far as Uruguay, after Interpol detected that Goretti had illegally exported to that country a number of the archaeological objects he was unable to exhibit in San Telmo, adding them to the Montevideo Museum of Pre-Columbian and Indigenous Art.

This case was forgotten. However Mateo Goretti again created controversy in 2007, when he donated 5,170 pieces to the Government of Salta, including photographs and archaeological and ethnographic objects, as well as a library of almost ten thousand volumes and specialist publications. With this donation, the collector sought to create the Argentinian Museum of Pre-Colombian Art (MAPA) and a foundation to administer it. But once again, his ambitions collided with the law. Now he has to explain to the justice system how he purchased the goods stolen from the Ambato Museum in Cordoba, when and from whom.

THE FALSE PAPERS

In October 2012, frequent deliveries from Peru of handicrafts arriving at Salt Lake City in the state of Utah in the United States, came to the attention of agents of the Immigration and Customs Service. Boxes were being sent to a husband and wife, César and Isabel Guarderas, two Peruvians nationalized as United States citizens, whom the Office of Investigations of the Homeland Security Department began to watch. It was discovered that the pair formed part of a network of traffickers of cultural artifacts using authentic handicrafts export certificates to hide their crime and who boasted about their links to employees of the Ministry of Culture in Lima from whom these certifiactes had been obtained.

The investigation started when an undercover US police officer sought out César Guarderas, aged 70, making himself out to be a client interested in the ceramics pieces being offered by the supposed expert in Pre-Hispanic art. Not long into the negotiations, the seller confessed that the items that he was offering to a select set of clients carried a higher price tag than that normally asked in shops, as they were not replicas, but were instead original pieces taken from archaeological sites in the north of Peru. The investigations moved to a second stage: the agent purchased two Chimú ceramics for three thousand dollars and then requested the assistance of specialists from the universities of Utah and Tulane to ascertain their authenticity.

The Office of Investigations intercepted the telephone and email of César Guarderas, while its undercover agent agreed a second purchase of ten ceramics for twenty thousand dollars. During their conversations, Guaderas mentioned the names of his suppliers: the Peruvians Javier and Alfredo Abanto Sarmiento, who were his wife´s brothers and owners of an apparent handicrafts business in Trujillo known as Cholo Andino, which had opened in 2008 and still operates. The suspicions that it operated as a network of traffickers in cultural goods were corroborated by the written communications of the suspects intercepted by the police and which became part of the case put by the Salt Lake City prosecutor. In a chain of emails between César Guarderas and Javier Abanto, they discussed a lot consisting of 100 pieces of original Chan Chan ceramics that would be exported to the United States in 2012 with commercial certificates facilitated by their contacts in the Ministry of Culture.

In December of the same year, the agents impounded one of the final deliveries which arrived from Peru directed to the Guarderas. The box contained eight Pre-Hispanic ceramics which had been sent by Javier Abanto. Shortly afterwards, more pieces were found in the garage of the couple´s home in the city of West Valley. Each was subjected to expert analysis and found to be authentic.

Javier Abanto Sarmiento was detained by agents of the Office of Investigations in Miami on 4 March 2013 on his way to the United States from Peru. César and Isabel Guarderas were arrested weeks later at their home. A court in Salt Lake City brought them to trial for smuggling and illegal transport of cultural artifacts, but they were released on a good behavior bond. The fourth suspect, Alfredo Abanto Sarmiento, who was in Peru, was not detained. The Ministry of Culture did not open any investigation into the case and has refused to make public the register of all persons and businesses with export certificates of goods not forming part of cultural heritage. “This information is commercial-in-confidence”, it said in response to a request we made for this report. Nor did the Peruvian prosecutor conduct follow-up to identify the role of employees of the Ministry of Culture in the Abanto-Guarderas case.

The last trace of the Guarderas is the telephone number of the home in Salt Lake City, but it is now disconnected.

The United States is one of the biggest markets for the trade of stolen cultural artifacts and Latin America is one of the principal areas of origin for this prized merchandise. In 1997, following the theft of the famous breast plate of the Lord of Sipán which was being sold in Philadelphia by a network of traffickers headed by the American David Swetnam, the US Government signed with Peru one its first memorandums of understanding imposing restrictions on the importation of Pre-Columbian archaeological objects and colonial ethnographic materials. The agreement meant that six years later, the Immigration and Customs Service was able to undertake a special investigation into cases of illicit transport of and trade in cultural objects in the United States, with the support of intelligence agents.

It was also through a covert operation that the Italian archaeologist and collector Ugo Bagnato was detected. He was regarded as one of the principal traffickers of Colombian and Peruvian Pre-Hispanic pieces into the United States. In September 2005, a Homeland Security agent in Florida pretending to be a client, purchased for two thousand dollars, a 3,500-year old ceramic together with a gold-nosed statue and approximately 1,800 years of antiquity. Experts from the Florida International University and the Smithsonian Museum in Washington DC confirmed the authenticity of the pieces. The police then entered Bagnato´s house and discovered that he had more than 400 Pre-Columbian objects stored in boxes, including including pottery, as well as gold and emerald ornaments.

At first, Bagnato defended himself with the argument that the goods had been imported legally and belonged to his private collection. But this alibi soon fell apart when Homeland Security proved that the documents used to substantiate their origin were false. Bagnato was found guilty of trafficking in stolen cultural artifacts and was sentenced to 17 months in a federal prison in southern Florida. In 2007, while serving his sentence, the American Gemological Institute based in San Diego (California) reported to Homeland Security that Ugo Bagnato had offered it more emeralds for valuation. Following a study of the gems undertaken by the University of Maine, the authorities established that they were authentic and part of Pre-Columbian artifacts stolen from Colombia.

Once he had completed his sentence, Bagnato was deported to Italy and in 2008 all the items were repatriated to Peru and Colombia. However, the suppliers were never identified because neither of the affected countries initiated local investigations.

Ugo Bagnato, 75, appears today in an Italian directory of art collectors. He owns a registered antiques house called Il Collezionista, although its operations are suspended.

Homeland Security also detected trade in Mayan pieces extracted from archaeological sites in Honduras which entered the United States with false documents claiming them to be handicrafts destined for a large store in the state of Ohio. The case dates back to 2002, but while the American implicated was sentenced in that year, it wasn´t until May 2016 that a judge in Tegucigalpa found guilty his two accomplices, the Hondurans Julio Monterroso Bonilla and Constantino Monterroso Palomo, sentencing them to prison terms for the crime of smuggling 275 cultural items to the United States. The artifacts were destined for Douglas Hall, an American, and proprietor of the antiques house Accent on Wild Birds, who served 18 months in jail. Hall died in 2005.

THE UNTOUCHABLE ANTIQUE DEALER

The commercial art and antique circuit in Mexico revolves around one man: Rodrigo Rivero Lake, a 66 year old lawyer and owner of one of the largest antique stores in the country, famous for his antique shopping trips to China and Indo-China. His name appears not just in galleries and museums, but also in the investigation of one of the most scandalous Mexican religious art thefts and one that the General Prosecutor is keeping closed. This case concerns the colonial painting Adán y Eva arrojados del paraíso, that, after being stolen from a church in the state of Hidalgo in February 2000, came into the possesion of Rivero Lake, who that same year sold it for 45 thousand dollars to the San Diego Art Museum.

In July 2002, when the curator of the museum, Claudia Laos, was cataloguing the painting, an internal investigation began that revealed it to have been stolen from the Church of San Juan Tepemasalco. In her search for information, Laos found a book by Agustín Chávez about the art of Hidalgo and on page 324 saw a photograph of the painting and a note indicating its origins in the church. However, the seller, Rodrigo Rivero Lake, had omitted this information and had also obtained an official document indicating that the colonial painting from 1728 was not part of the collection of the the National Institute of Anthropology and History (INAH) even though it had been reported stolen. Two years later, the Mexican General Prosecutor began an investigation based on the information provided by the San Diego Art Museum, but never provided an update on the case, which is now considered closed. “Everything is archived”, the main suspect assures us from the comfort of his luxurious penthouse in the exclusive suburb of Polanco.

Until now, Mexico´s star antique dealer has never responded to the questions about who sold him the picture. “This is all very upsetting. They began a campaign to discredit me (…) It is not that the collector or the antiques dealer is the looter. This idea needs to change. Often we are the protectors”, says Rivero Lake in his defense, during an interview for the Stolen Memories project.

The art seller claims that he has never been to the church in Hidalgo from where the painting was stolen. Over time he has given several versions about how he came to acquire the work: that he bought it from an antique dealer in the United States, that a group of elderly women in Hidalgo obtained it saying it belonged to their family and that is was bought by a patron of the arts. The Mexican Prosecutor General refuses to provide information from file AP/PGR/HGO/PACH1-III/039/2005. “It is reserved for a period of five years because it relates to information linked to the prosecution of a crime”, was the response to a request from this investigation.

The United States Government returned the oil painting to Mexico through diplomatic channels, but the Prosecutor has not even reported if the people who participated or had responsibility in the theft and illegal sale and export of the painting to the museum in San Diego have been identified.

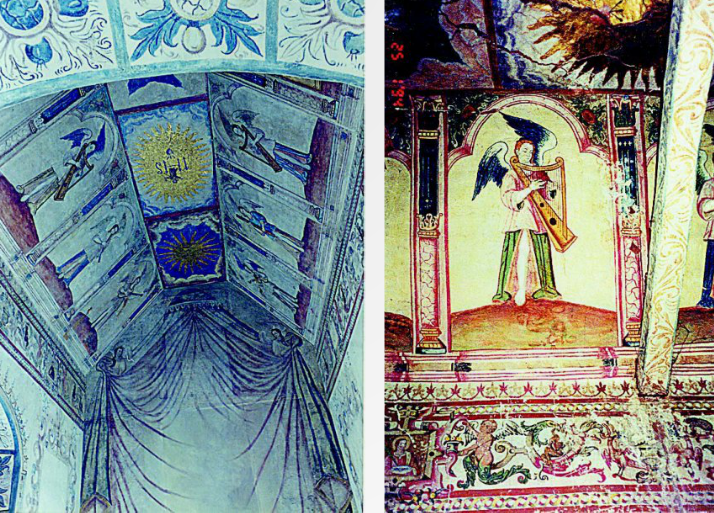

Rodrigo Rivero Lake was investigated in this case and his name also appears as a suspect in another Latin American cultural artifacts trafficking scandal. In 2004, the reformed Dutch art trafficker Michel van Rijn, revealed that the Mexican antiques dealer had offered him the charts and the photographs of the Coro de Ángeles mural from a 17th century Peruvian chapel with the intention of selling it to him for one million dollars.

The work had been stolen from the Tongobamba estate in Andahuaylillas, Cuzco, and formed part of the Andean Baroque Route. How did it come into the possession of Rivero Lake? This is another another unanswered question which the art seller has refused to clarify up to now. The Peruvian National Institute of Culture (INC) filed a complaint against him, but a prosecutor in Cuzco archived it in 2005.

When the case came to light, Rivero Lake was President of the Board of Sacred Art in Mexico and declared that he bought the mural during one of his visits to Peru at the end of the 90s from a group of Andahuaylillas residents who had become evangelicals and were threatening to destroy it. However, between 2004 and 2006, the INC and the Cuzco Regional Culture Directorate demonstrated that the painting had been stolen and should be returned to Peru. The recovery process was delayed during the second Alan García government, over a period in which the historian Cecilia Bákula headed the INC.

Copies of the studies which prove the origins of the mural are still kept on the files of the Franklin Pease Collection about the Andean history of Peru. The historian Mariana Mould de Pease, who collaborated with Michel van Rijn in the investigation of this case, has a copy of letter number N°363-2005-MP-FPT of the Cuzco Provincial Tourism Prosecutor. This rejects the INC´s request that the Mexican antiques dealer be investigated for an offense against cultural heritage in the category of extraction of artifacts against the state. Rivero Lake prefers not to speak about this matter. “There are things that you have which are stolen before you are even born”, he says, to explain how it can be that the owner of a stolen work of art is not necessarily guilt of its theft.